Recently, I ran across some news reports about a neighborhood that was fighting a new townhouse project on some adjacent property on the basis that it would degrade drainage in their area. There is so much misinformation out there right now about the dynamics of flooding that I was frankly a bit skeptical when I first read the reports, wondering if this was not just some NIMBYism cast as flood concerns.

But as I dug into the situation, a truly remarkable tale unraveled that is a great illustration of what has gone so terribly wrong with our flood policy in Houston. I apologize for the length of this post, but if we are going to get flood policy right in Houston it is going to take this kind of deep dive.

Let’s start with the physical setting. Timbergrove is a quiet, wooded subdivision tucked in the northeast corner of Loop 610 along White Oak Bayou. The section that has raised the most concern about the new townhouse project is an area with a little over 100 homes, just south of W. 11th and west of the bayou. The neighborhood took a major hit in Harvey, with about 80% of the homes suffering some flooding. The damage in about 20 houses was so bad that they had to be demolished. About a half dozen lots have been or are scheduled to be purchased by FEMA.

Just to the south of this neighborhood is a railway and a gravel storage yard. An approximately 300-foot wide, heavily-wooded strip of land separates the neighborhood from the rail facilities. There is a gully on this wooded strip that carries floodwater from the subdivision and the rail facilities east to White Oak. There is a small parcel between the gully and railroad that appears to be almost entirely in the 100-year floodplain. It is this parcel on which the developer plans to build 77 townhomes to be known as Stanley Park.

Why anyone would be developing townhouses in the 100-year floodplain and in an area that flooded badly in Harvey is beyond comprehension. I also cannot imagine who will buy or finance the townhouses. But laying that insanity aside, understanding why this area floods goes much deeper than just this proposed development.

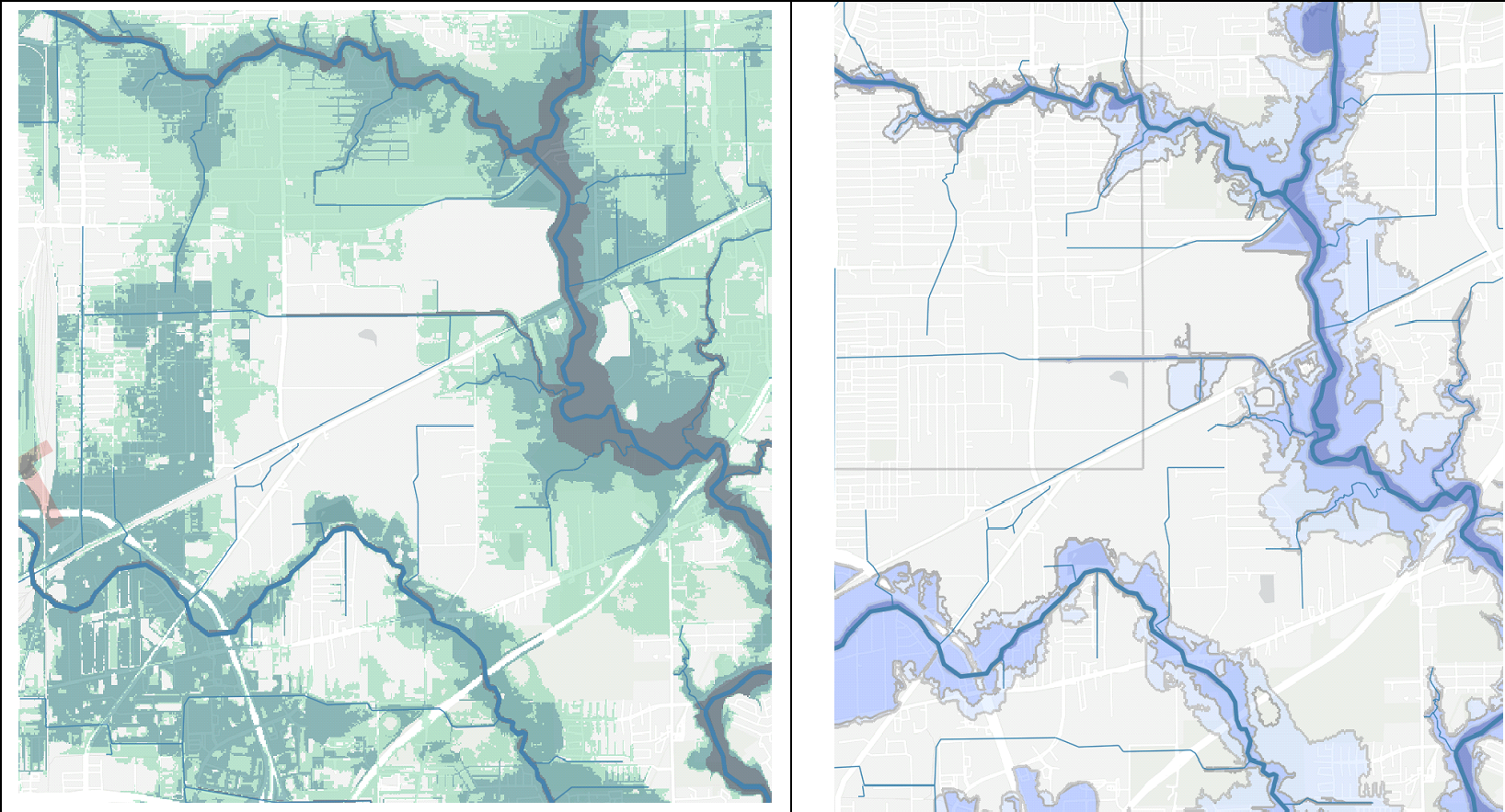

The earliest aerial photo of the area I could find was 1944. The railroad was there at that time but not the subdivision. White Oak bayou had not yet been channelized and instead meandered through the area. In fact, the gully between the neighborhood and the proposed development was, at that time, part of the main channel.

The next photo is from 1953 and shows the channelization of White Oak and the beginning of the development of Timbergrove Manor. From what I have been able to determine, the consensus of the engineering community at the time was that the channelization of White Oak would keep a 100-year event in the banks of the bayou.[i] In retrospect, it would clearly have been better to elevate the subdivision, but instead it was mostly built on the existing grade.

After the development was completed in the 1950s the railroad continued to expand its facilities, filling in more of the old bayou bed. A comparison of the 1953 and 1978 photos shows how dramatically the drainage was restricted by the filling the railroad did during that time period. As a side note, I have found dozens of instances across the region where the manner in which railroad facilities have been developed has greatly exacerbated our flooding problems.

The City had an opportunity to improve the drainage in the area in the late 1990s when the railroad sold the area adjacent to TC Jester and White Oak bayou to an apartment builder. The City dutifully permitted the development and the developer built the Stonewood Apartments, which you can see in the current photo above. Had the City denied the permit and instead condemned the property for a detention area and removed the fill the railroad company had placed there, we would likely not be having this controversy today.

Ironically, it also appears that flooding in the area was made worse by a hike-and-bike trail that was installed by the City along White Oak Bayou in 2015. The trail has a bridge over the gully that restricts the flow down to just two culverts. This bridge had to be a significant impediment to floodwater runoff during Harvey.

So, that brings us to the current controversy. Another developer acquired the strip of land between the gully and railroad and in 2010 proposed to develop townhouses there. The City was so keen to see the project built that it entered into a “380 agreement” on the project. In 380 agreements, the City agrees to reimburse developers part of their development costs as an incentive to spur development. So not only was the City prepared to allow a developer to develop in the 100-year floodplain and in an area known to flood, it approved using taxpayers’ money to subsidize it!

The project was originally permitted in 2012. By that time, for a project to be permitted in the floodplain, the developer had to show that it would not create additional floodwater runoff onto surrounding properties. Generally, this takes the form of some kind of detention.

Apparently, the City granted the 2012 permits on the theory that the developer had some detention “credits” in the area. This can occur when a developer has nearby property that would be set aside to mitigate any additional runoff. But there were two problems.

First, this was not a case where nearby retention would do any good. The filling the railroad did in the 50s-70s had essentially partially dammed the gully. No additional retention is going to keep the sheet flow from the neighborhood from stacking up against that obstructed area and backing up into the neighborhood.

Second, and you are going to love this, after 2012 the developer sold the land that served as the detention credit to TxDOT to mitigate its runoff from an I-10 expansion. By the way, for the princely sum of $5.2 million of your taxpayer dollars. So, when the project finally got underway in 2018, the detention credits on which the project relied (even though they are worthless from the standpoint of actually keeping the neighborhood from flooding) were long gone.

Nonetheless, this last April 20 (less than 240 days after Harvey), the City issued this “floodplain development permit” to begin construction.

At the June 26 City Council meeting, a number of residents appeared to protest the project. Turner told them that the project was “on hold.” However, it does not appear the City had actually taken any action to stop the work at that time, as crews were back at work the next day. On July 2, the City did finally issue a stop-work order, but only for ten days and based on some relatively minor technical violations.

Turner also said in the meeting that there were a number of “eyes on this project.” Yet, only a month earlier, David Lopez, a senior floodplain inspector with the City, had inspected the site in response to residents’ complaints and concluded that “[t]he site has an approved commercial Fill/Grade Development Permit for a future subdivision.” [Read the email exchange here.]

There is no doubt that if the Stanley Park project is allowed to go forward, its future residents will be at risk of having their homes flooded and it will make flooding in the area worse. Fill is being brought in to get the project up to the current standard (100-year flood plain + 1 foot) and it apparently has no compensating detention. Also, the access to the project is across the gully. Any type of crossing almost certainly will further restrict flow. So, this is just an all-around bad idea.

What happens next remains to be seen. The developer can easily resolve the technical violations cited in the stop-work order. So far, no one at the City has indicated they intend to try and stop the project altogether. Nor has anyone said if the City intends to honor the 380 agreement and use taxpayer money to subsidize yet another project to be built in the floodplain that will almost certainly make flooding worse for the residents of Timbergrove.

The best resolution would be for the City to condemn the property for a drainage easement. According to the Harris County Appraisal District, the lots currently have a market value of about $16,000 each. So, the entire property should be worth something in the $1.2 million range. That is only about 1% of what Houstonians are currently paying in drainage fees and only about 2% of what the City paid for the tiny strips of land to build the Post Oak bus boondoggle. So, it is not much of a lift from a financial standpoint.

But unfortunately, the recently approved City budget allocated most of the drainage fees to balance the general fund and for various pet projects, completely unrelated to drainage. And, of course, the City is shy about condemning property of major campaign contributors. Nonetheless it is exactly the kind of use to which those fees should be put. But I wouldn’t hold my breath . . . even though the residents of Timbergrove may have to do exactly that in the next flood.

You can read more about and support the Timbergrove’s resident fight to stop this project at Stop Stanley Park.

[i] The City did not begin participating in FEMA’s flood mapping regime until 1978. So, at the time this subdivision was developed the floodplain regulations we know today did not exist.