In the wake of the two recent devastating hurricanes, the nation is once again focused on the personal tragedies and unsustainable economic costs of tropical cyclones. Virtually all of the media coverage has focused on the effect of climate change on the frequency and intensity of these storms. However, the focus on climate change, to the exclusion of other factors, risks not implementing effective policies that could mitigate the damage done by future storms.

The dynamics of a tropical cyclone are about as complicated a phenomenon as the human mind can imagine. And while our understanding of their mechanics has vastly improved in the last two decades, they are still wild, untamed beasts that defy our predictions. We are especially in the dark about when, where and why they will appear.

I believe that the current state of our understanding supports the proposition that a warmer climate is making, and will continue to make, tropical cyclones worse. However, it is inaccurate to claim that climate change caused a particular storm, which I regularly hear in the media. Tropical storms have been ravaging the southeast U.S. for thousands of years and they will continue to do so regardless of the future trajectory of the climate.

Nonetheless, the temperature of the oceans is unquestionably a significant factor in the formation and strengthening of tropical cyclones. I think the best way to think about the effect is that rising ocean temperatures are setting a higher baseline for the frequency and intensity of storms, on top of all the other factors that affect their normal variability.

How much warming is resetting that baseline is subject to a great deal of speculation but there is no scientific consensus on that degree, despite the nonsense that you read in stories like this one from the New York Times, which claimed Milton may have caused the twice damage because of climate change.

The Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, a NOAA agency, issued a periodic assessment of the effect rising temperatures are having on tropical storms. The latest discussion in 2023, noted that “several Atlantic hurricane activity metrics show pronounced increases since 1980.” However, it was inconclusive as to the degree these increases could be attributed to warmer temperatures:

“While greenhouse gas-induced warming may have also affected Atlantic hurricane activity, a detectable greenhouse gas influence on hurricane activity has not been identified with high confidence. This is partly due to the masking of any century-scale trends by pronounced multidecadal variability . . .”

The GFDL’s models project about a 10-15% increase in the number and severity over the balance of this century attributable to warmer temperatures.

However, the economic damages from tropical cyclones have been increasing much more dramatically than the increase in storm intensity noted by NOAA. This is a chart of the damages by decade prepared by NOAA. The values have been adjusted for inflation. Note that the current decade is on track to blow past 2010-2019, especially after the storms of the last couple of months.

So, according to this accounting, economic damage done by recent storms is running more than ten times worse than forty years ago. Clearly, tropical cyclones have not gotten ten times worse. So, how do we explain that increase in damages that is so disproportionate to the observed increase in tropical cyclone activity?

Certainly, part of the explanation is that we have put many more people and investments in the path of storms. This study from NOAA found that the population in coastal areas vulnerable to Atlantic storms increased from about 12 million in 1970 to about 30 million by 2020.

Compounding putting more people and building more in vulnerable areas, there were lackadaisical building codes that persisted for decades. It was really not until the mid-1990s that local and state governments began to tighten their codes. And in some cases, the enhanced regulations came even later.

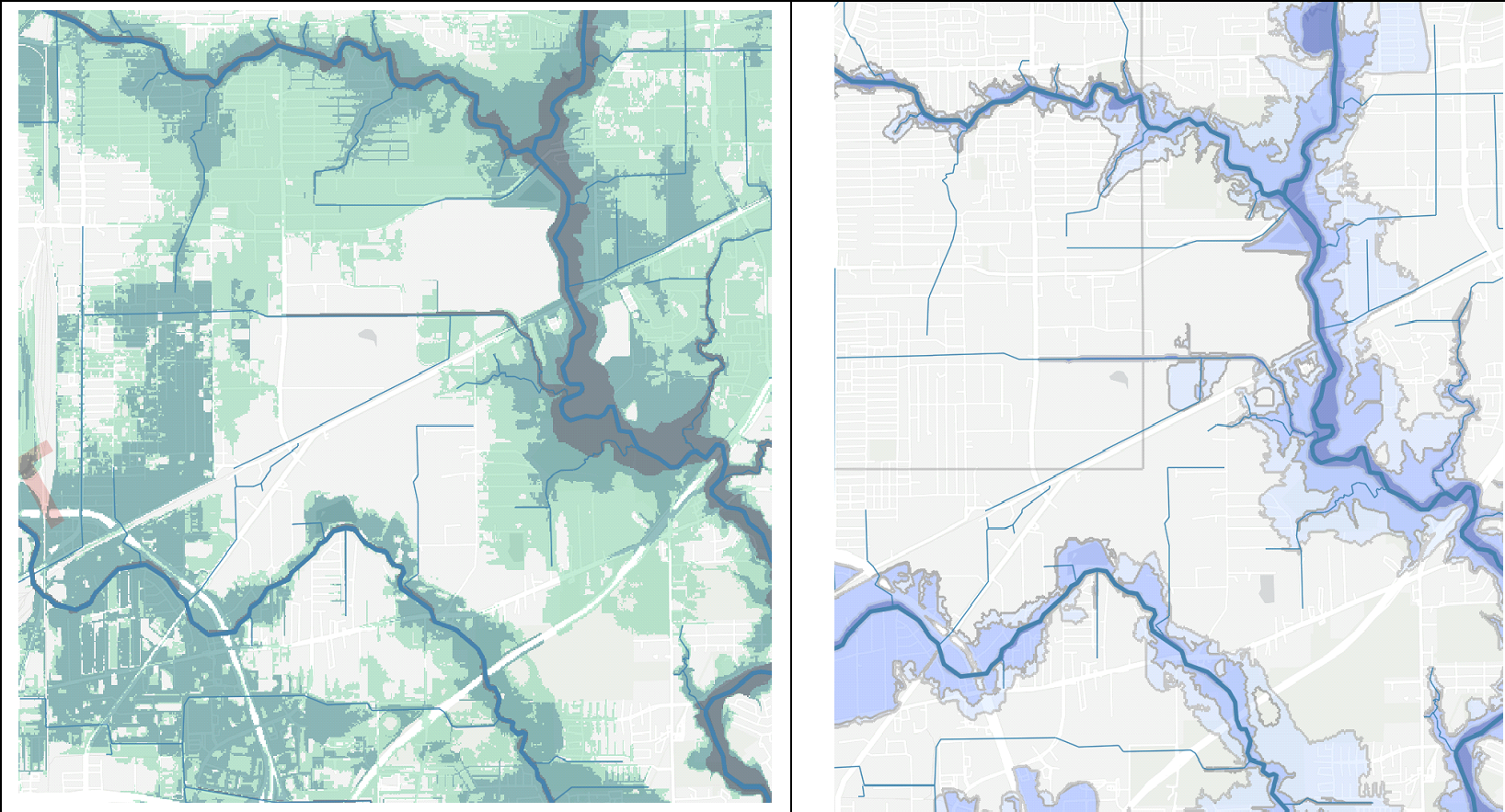

Also, jurisdictions allowed construction in flood prone areas for far too long. Most flood zones have only recently been updated in most jurisdictions. In fact, we actually subsidized building in flood prone areas by providing flood insurance at rates that did not reflect the risk. That has only recently begun to change because the national flood insurance program was becoming financially unsustainable.

There has also been a lack of political will to make some of the hard decisions. When I chaired a task force in the wake of Hurricane Rita in 2006, we raised the question about whether nursing homes should even be allowed in evacuation zones. We also proposed posting markers along highways that show evacuation zones and previous flooding levels. Because of political pushback from the nursing home and real estate industries neither proposal got any traction.

It is the confluence of an increase in tropical storm activity, dramatic population growth in vulnerable areas, which we incentivized by providing subsidized flood insurance, and the lack rational regulation that has created, if you will pardon the pun, the perfect storm.

The real question is how do we address the problem? More on that soon.

.png)