In 2017[i], the US population grew by 2.3 million, a 0.7% increase (that is 7/10s of one percent). We have been running at about this rate since 2010. However, it is well below the post WWII average of about 1.2%. The only other time in our country’s history that the population growth was this slow was in the Great Depression. Of course, the most rapid population growth came immediately after WWII with the now-famous Baby Boom. There were “echoes” of the Baby Boom in the early 1970s and early 1990s. But since then the growth rate has slowly and steadily declined.

In recent decades, about 60% of our population growth has come from a “natural increase”, that is the number by which women living in the US had more babies than people who died. About 40% of the increase came from immigration.[i] That has equated to natural population growth of about 1.2 million per year and about one million coming from immigration.

This means that if the US had not been allowing any new immigrants, our population would actually be falling by now. While that may not seem immediately intuitive since the natural population growth has continued to exceed immigration, it is the case because once new immigrants are here they become part of the natural growth. That is, had the US not admitted 10 million immigrants in the last ten years, there would have been 5 million fewer women contributing to the natural population growth.

The “fertility rate” is a demographic term which refers to the number of children that each woman will have during her lifetime. For a population to grow, the fertility rate must be something just over two because to just maintain a stable population each woman must have two children to replace her and her mate and a little spare for children who die before reproducing. The breakeven fertility rate is about 2.2.

The fertility rate in the US today is about 1.8. The last time it exceeded 2.2 was 1971. In 1957 it was 3.7. Now, you might wonder if the fertility rate is already below breakeven, why our natural population has not already begun to decline. There are two reasons. First there is a wave-like effect from previous periods of high population growth, like the echoes of the Baby Boom we saw in the 1970s and the 1990s, as the growth subsides over the next several generations. Also, people are living longer so we have fewer deaths per capita.

As a result, the Census is projecting that US population growth will continue to decline and essentially come to a full stop sometime the late part of this century.

The US is not alone in this phenomenon. Projections by the UN and World Bank also show the world population topping out sometime mid-century. The world fertility rate is already below breakeven and some countries, like Japan, are facing significant population declines in the next two decades.

We tend to simultaneously hold two contradictory notions about population growth in our minds. Ever since Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s 1968 bestseller, The Population Bomb, the public has generally viewed population growth negatively. Polls show that about 60% of Americans think population growth is a major problem. Yet we at the same time celebrate the growth of our local city or even our state as an indicator of success. We have these contradictory ideas because one is a long-term view and the other is short-term.

Basic economics teaches us that economic growth is essentially the sum of population growth and productivity increases.[ii] That is why we celebrate population growth of our city, for example. We know intuitively that more people in our town means more customers for restaurants, grocery stores, car dealers, etc. That in turn means more jobs and likely higher incomes for everyone . . . a rising tide lifts all boats.

But we also know that we live in a world with limited resources that cannot support indefinite population growth. And though technological advances have staved off the apocalyptic predictions of the Erhlichs and others, you can only stretch a rubber band so far.

But our short-term view that population growth is “good for business” is nonetheless true. The deceleration of population growth will be a drag on economic growth. There are many things we could do to make our economy more productive. Technology will certainly play the pivotal role in that regard. And we could help with better policy. While I think the Republican tax plan was largely a shell game to pay off its donors and will produce little growth, rolling back oppressive regulations could yield a great deal. It would be nice if we also had some regulatory reform at the state and local levels as well, but good luck with that.

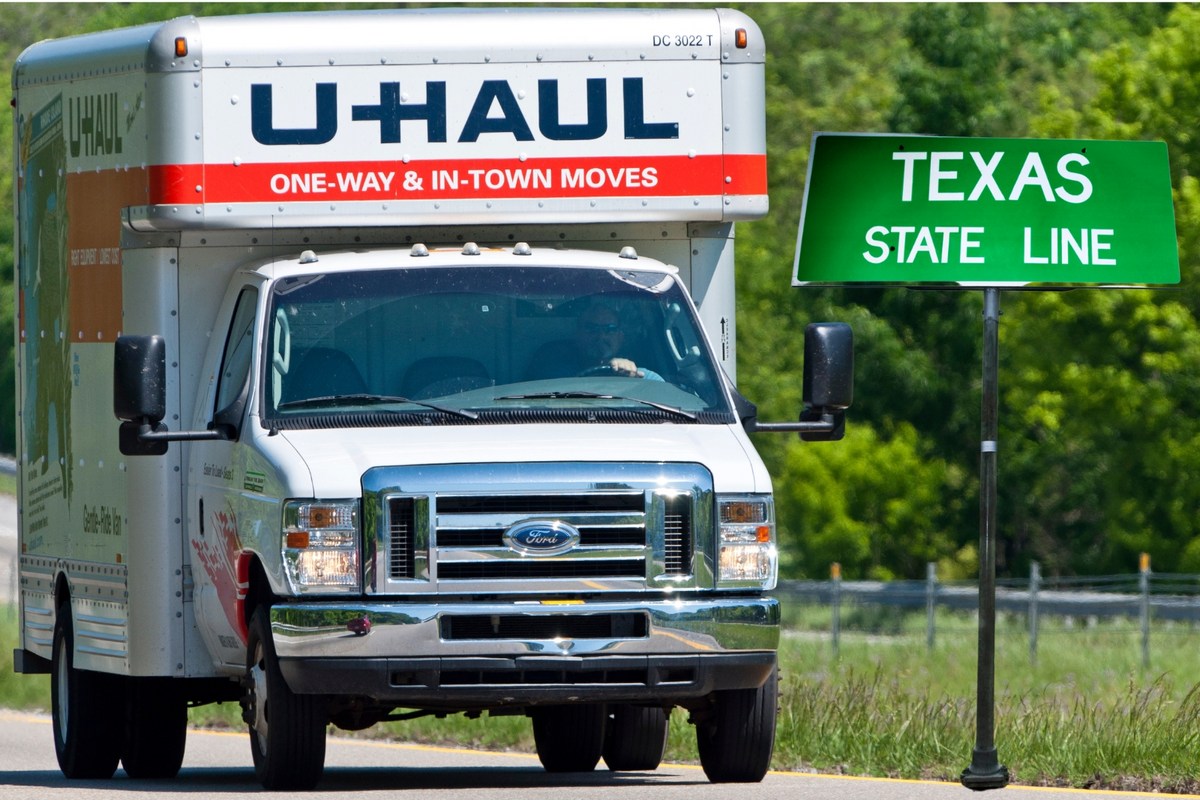

Of course, the decline in population growth also begs the question about what our immigration policies should be. While the populist notion that immigrants take away jobs from Americans may be true in specific cases, it is unquestionably true that more immigration will improve overall economic growth. The degree to which it helps is determined by the quality of the immigrants admitted in terms of how prepared they are to contribute to the economy. Obviously, allowing entry to immigrants that have no intention or ability to work will do little to help the economy and might actually hurt it. The same with criminals.

But it is also a mistake to say that we are only going to allow in highly educated immigrants, because the US economy will have an acute need for service workers in the future that do not necessarily need to be highly skilled. Think about how many people we are going to need to take care of Alzheimer’s patients in 20 years.

Immigration hawks are right that we need to be smarter about the manner in which we admit people to our country. And the level of immigration needs to be controlled to match the country’s needs. But anyone who thinks the country would be better off economically if we had not admitted 10 million new residents over the last decade or that the country would be better off financially if we deported the 10 million immigrants who are here illegally, does not understand basic economics.

[i] The US Census Bureau estimates are from July to July

.[i] For purposes of counting population, the Census Bureau includes immigrants whether they are here legally or not.

[ii] There is a very significant debate within economics today as to whether traditional measures of GDP and productivity are valid in digital age. A discussion of that issue is beyond today’s scope, so I will stick with those traditional concepts for now and discuss the how they may be obsolete in a future post.